The short film Myth (18.5 minutes) is available at the top of the page.

* To watch this film, please approve YouTube/Vimeo cookies via the blue cookie icon at the bottom left of the screen.

A young man dressed in a military uniform moves through a house, a flashlight switched on and a gun in his hand. He navigates the dark interior while documenting his actions on his phone. Yet, between the beams of light, a paradox begins to unsettle this initial assumption that what we are witnessing is a military operation. Doubt emerges for several reasons: he is alone, he carries no radio, and his clothing, despite its combat-like appearance, does not match the standard uniform of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

The young man bursts into a bedroom, waking an older man from his sleep. It is evident that the older man recognizes the intruder and is startled both by the sudden awakening and by his presence in the room. The young man orders him to get up and film him with the camera. When the older man addresses him by the name “Ohad,” and the young man corrects him, insisting that his name is “Liraz,” the viewer’s uncertainty deepens, further destabilizing any clear understanding of the situation. He then instructs the older man to return to bed, keeping the camera running, to continue documenting the scene. The young man resets the broken door, staging a deliberate re-enactment of the event, before bursting in once again and shouting, “IDF, this is not a drill.”

From this point on, the film Myth takes these two characters and the viewer on a journey that continues to blur, confuse, and undermine the objectivity of the image, the essence of filming, and the power relations between father and son, framed as an allegory for the relationship between the state and the citizen.

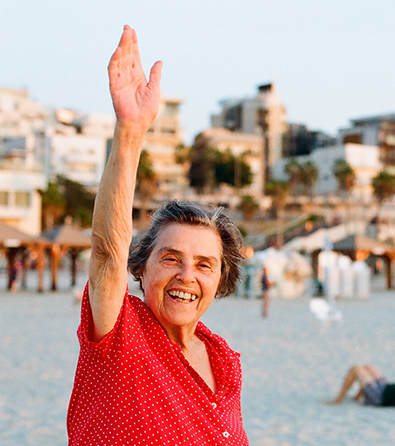

The following scene places a clear emphasis on the photographic image: the young man films himself on his phone in a manner reminiscent of social media live streams. Meanwhile, the older man, whom the young man addresses as “Dad,” scrolls through his own phone. The young man remarks that his father is a recent recipient of the Israel Defense Prize, despite having served not in a combat unit but at the IDF headquarters. The father, however, responds with indifference, his gaze fixed on the screen, as though this situation was already familiar to him.

Further cracks begin to surface when the father once again calls his son “Ohad,” while the son retreats into the persona of Liraz, a combat soldier who, according to his own account, “has seen terrible things.” Throughout their journey together, contradictions and gaps continue to emerge in the dialogue between them. These include inconsistencies regarding the son’s military service, the gun that is eventually revealed to be fake, and the father’s repeated attempts to calm his son and pull him out of his “episodes.” The truth is further destabilized when the father claims that his son accuses him of having prevented his enlistment in the IDF.

So, what is the real story? The film deliberately misleads, raising questions about the nature of reality and fiction. Midway through the film, a non-diegetic transition shifts the scene into a cinematic green-screen studio, where Ohad sits inside a car surrounded by professional lighting equipment. The means of production are thus exposed, revealing the underlying narrative and destabilizing the boundary between reality and fiction.

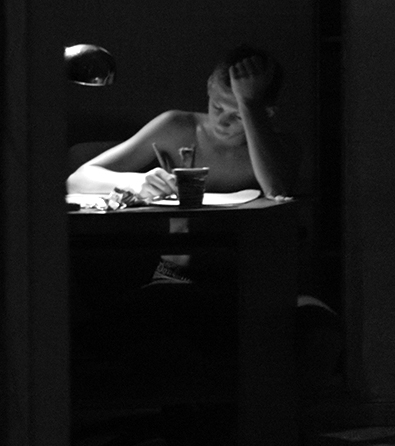

The young man looks directly into the camera and recounts a military story in which he claims to have taken part, a narrative that may be understood as the source of the trauma that continues to haunt him. This account is illustrated through combat scenes that the film abruptly cuts to, appearing as involuntary flashes in which the trauma resurfaces. It is not only the exposure of the means of production and the breaking of the fourth wall that reveal the narrative truth, but also the “flashbacks” themselves, which attentive viewers will recognize as shots taken from the film Lebanon (2009), directed by Samuel Maoz. The father’s voice, which pulls Ohad back into reality and into the film’s diegetic space, further disrupts the illusion of the story Ohad is telling the camera. His fabricated memories continue to haunt him, ultimately driving him toward a violent confrontation with them in a masochistic manner.

This constant play between fiction and reality reveals the film’s distinctiveness. By drawing a parallel between the father and the son, the film uses both characters to examine military trauma. In his book The Anxiety of Influence, literary critic Harold Bloom explores the relationship between early poets and those who follow them. Bloom argues that every new creator exists in the shadow of successful predecessors, who function as “spiritual fathers,” and that the artist must find a way to contend with these influences. From his Freudian perspective, Bloom claims that the “son” must perform a violent act upon the art of his “father” to free himself from the chains of influence, recreate himself, and ultimately discover his own authentic voice.

Myth performs a double move. Ohad invents a military combat narrative to contend with earlier filmmakers who addressed this very subject, while simultaneously confronting the military ethos and the intergenerational trauma embedded in the Israeli military experience. The film foregrounds the traumatic nature of military service and the impulse of the younger generation to measure its experience against that of the fathers’ generation, to equal it, and even to surpass it. This impulse often leaves each generation marked by trauma. A clear parallel can be found in Samuel Maoz’s second feature film, Foxtrot, in which the drive toward combat leaves Israeli masculinity wounded and dysfunctional. Based on this traumatic foundation, Myth links personal trauma with collective trauma through its use of war scenes drawn from other Israeli films. Beyond excerpts from Maoz’s work, the combat sequences also incorporate footage from Waltz with Bashir by Ari Folman. The film argues that even those who did not serve in combat units’ experience collective trauma through shared images of war, images that circulate widely and are repeatedly reenacted through cinema.

This collective trauma helps explain Ohad’s urge to document himself and to articulate his identity through the camera. As Bill Nichols argues in his essay Documentary Reenactment and the Fantasmatic Subject (2008), reenactments seek to be recognized “as a representation of a prior event while also signaling that they are not a representation of a contemporaneous event.”. In other words, reenactments aim to create a present-day representation of a past occurrence yet still demand to be treated as a credible account. Within Israeli society, those who do not serve in the IDF are often subject to criticism. Consequently, Ohad, who did not experience military service firsthand, attempts to produce images of himself as a soldier by staging and reenacting military scenarios for the camera.

Thus, the act of documenting the situation becomes a central component of the event itself, functioning as a means of filling in what is missing and transforming an absent trauma into part of a collective one. To this end, the film weaves together cinematic images with Ohad’s own recorded images, as he seeks to transform himself into the heroic soldier figure of Israeli cinema.

Returning to Bloom’s initial formulation, the film may also be read as an attempt by its creator, Omer Melamed, to contend with cinema itself as a means of grappling with trauma. This effort takes shape through the extraction of existing film fragments from their original contexts, their appropriation, and their redeployment in the service of a different meaning. In this sense, the film can be understood as a way of engaging with earlier Israeli filmmakers and their approaches to military trauma, and ultimately of surpassing them.

How can military trauma be articulated through cinema without simply repeating what has already been done? Myth offers a distinctive response to this question. In the film’s final moments, Ohad enters a dark tunnel and begins to shoot. Are these the gunshots from earlier films, now returning fire? Is he shooting at himself? The film suggests that, in such a situation, the only possibility that remains is an act of violence directed inward, toward the self, whether as a person, a soldier, or a creator.