Watch the video and music installation Silence isn’t Very Much (42 minutes) at the top of the page.

* To watch this film, please approve YouTube/Vimeo cookies via the blue cookie icon at the bottom left of the screen

Silence isn’t Very Much is a three-channel video installation by artist and musician Guy Goldstein, based on his original songs from the album “Memorable Equinox.” Goldstein created the music during his stay in Northern Ireland in a two-hundred-year-old detention tower. The tower, originally intended for the imprisonment of idealists and protesters, is now used as a residence for international artists for residency and creation purposes. Goldstein’s works address the boundaries between text, image, sound and object. The characteristics that define these boundaries, such as color, shape, and time, relate to essential physical elements like wavelength or resonance in liminal states of language, music, or image. As a visual artist who also writes and composes music, Goldstein explores the connection between the visual and the auditory, attempting to decipher concepts such as ‘noise’ and ‘silence’ by examining contemporary and historical religious and political conflicts and understanding the auditory and musical influences they have on society.

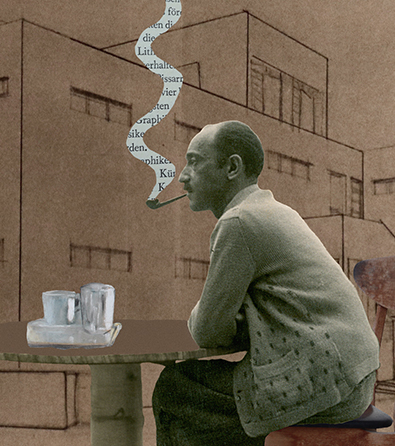

The video art installation Silence isn’t Very Much addresses the conflict in Northern Ireland by exploring the role and historical function of the artist as a preserver and recreator of events and mythologies. In the video art, Goldstein transforms the small, low-ceilinged space in the tower where he resides into a laboratory of historical sounds. He creates a parallel between the processes of creating an artwork from the conceptual stage to execution and the processes of building a protest and a dissenting language. For example, the screen is divided into three screens, in some of which Goldstein is seen listening to sounds or creating sound in the tower. In contrast, in parallel windows, the film’s protagonists are seen in their daily work, mainly manual labor of the working class, such as sausage production and meat cutting. These visual images are interspersed with testimonies of bodily harm to protesters and government opponents and a FREE DERRY sign, a call for independence and autonomy in Ireland.

Goldstein discusses the autonomy of human expression within the conflict in Northern Ireland through the body and voice. He examines concepts of freedom and independence by exploring the intersections between language, soundtrack, and visual imagery, such as in the statement made by one of the subjects, “I will not see a world that will be dear to me.” He investigates the relationship between the land and the place—that is, the world—and the daily life and identity of the protagonists. Through sound, he performs an act that evokes the deep currents of resistance and conflict, examining both recent and distant history.

Goldstein walks the roads and paths of the Northern Irish village and tours local historical sites while dressed in the locals’ period clothing. The echoes of music, protests, and slogans are heard like a Greek chorus as the characters recount the harsh conditions in which they were imprisoned as opponents of the British regime, without a bed, toilets, aid, or freedom. Goldstein listens to the testimonies of the protagonists, delving into the archive and creating a new, vivid, electrifying experience from it, with one foot rooted in history and the other in the contemporaneity of creating a performative work of art in the making.

The performance of objects and items that accompany the film’s protagonists and Goldstein himself emphasizes the physical experience of art and protest. As a historical figure who reconstructs, the artist is present in the film as both an operator and a subject. On one hand, he listens; on the other, he creates and mixes his protagonists’ human, textual, physical, and vocal experiences. Goldstein explores movement as performative art—not only as a protest movement but also in other bodily senses, such as police running after protesters or Hurling players advancing on the field. These images, which parallel the prosaic and the protest, highlight the commonality and connection between the simple and straightforward language of the speakers and the issues and ideas they feel compelled to fight for. Their past experiences undergo a process of visual and vocal abstraction in the video art installation, where concrete ideas become mythical, like inscriptions engraved on an archaeological substrate.

Goldstein directly refers to the concept of “The Troubles,” commonly used in the context of the Northern Ireland conflict; “The Troubles” apparently disrupted political calm and the status quo. To create the video installation, Goldstein met with village residents—Catholics and Protestants, workers and artists, clergy and musicians—and asked their opinions on noise. He recorded sounds and conversations and researched Irish culture and mythology. All these elements are documented in the video installation, combining stories, sounds, and words with his playing and singing, creating a single work that captures the problematic complexity that still exists in this place, reflecting on other violent conflict areas around the world, and indeed on life in Israel and the Middle East.

Goldstein first created the album that served as the soundtrack for the video installation, and only afterwards did he create the artwork itself. The sound is played simultaneously from three audio channels, and the screen is split into three or four windows. The different narratives of the protagonists and the lives documented in the video art create a deliberate cacophony, forcing the viewer to consider noise and silence as human-made phenomena rather than as a predetermined fate of nature and the environment. Moreover, the video art emphasizes that creating change and historical shifts depends on making noise and vocal expression.

Goldstein’s use of instruments like the harp as a background to the testimonies suits the mythical and historical nuance the video artwork grants its speakers. Goldstein himself tries to find his place and roots in a foreign location; this is reflected in his actions in the public space, wearing historical clothing, and in his attempts to create a home in the private space of the detention tower, whose corners, walls, and ceiling are too narrow to contain. The concept of home is thus not only the physical, protected, and unattainable structure for Goldstein but also a national home and a tension between religious, collective, and political identities, which are an inseparable part of human existence and the history it builds.

Goldstein’s work Silence isn’t Very Much also references the music and cinema that marked the end of the conflict in Northern Ireland in the late 1990s, after more than thirty years of violence: “My Left Foot” (directed by Jim Sheridan, 1989), “The Commitments” (directed by Alan Parker, 1991), “The Crying Game” (directed by Neil Jordan, 1992), and “In the Name of the Father” (directed by Jim Sheridan, 1993). The stories of the Irish underground are depicted in these films, which also discuss the role of art, the life of the artist, and music as an integral part of the political conflict. Goldstein’s work references these films and music, reflecting on their portrayal of the political turmoil and the intersection of art, life, and music within the historical context of Northern Ireland’s Troubles.

Silence isn’t Very Much refers to the artist’s experience of observing the lives of citizens, the history, and the sounds that shaped the era and turned it into grand mythology. Between image and text, and between sound and silence, the civic perspectives expressed on the screen and through the different channels are like material in the hands of the creator, who examines the state of the artist and the perspective on the national narratives and mythologies that shape the political noise in their lives. Conversely, civic perspectives contribute to shaping the political and artistic narrative. The artist functions as a storyteller trying to gather pieces of human history and break them down into their physical components.

Silence isn’t Very Much is a three-channel video and music installation first exhibited at Goldstein’s solo exhibition “Once, a Beat, Second Hit” at the Petach Tikva Museum of Art in 2018, curated by Drorit Gur Arie.