Watch the short film Ronde de Nuit (22 minutes) at the top of the page.

* To watch this film, please approve YouTube/Vimeo cookies via the blue cookie icon at the bottom left of the screen

Julien Regnard’s 2021 short film, Ronde de Nuit (The Night Watch), is a cinematic exploration of the human psyche, resonating with the psychoanalytic intensity found in classic cinema. Regnard, acclaimed for his award-winning animated films such as “Somewhere Down the Line,” which earned the Best Animated Film award at the Clermont-Ferrand Festival, continues to push the boundaries of animated storytelling in Ronde de Nuit. He crafts the film in black and white using Blender’s Grease Pencil, resulting in a striking example of how animation can transcend traditional narrative structures to delve deeply into the realms of human emotion and experience.

The plot of Ronde de Nuit opens with a couple, George and Christina, leaving a high-society party at a lavish estate. The opening scene, rendered with stark contrasts of light and shadow, sets the tone for the nightmarish journey that follows. The party itself recalls the masked ball in Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999), where masks and dishonesty between couples conceal darker, more primal instincts. In both films, the veil of night reveals the characters’ fears and fundamental urges.

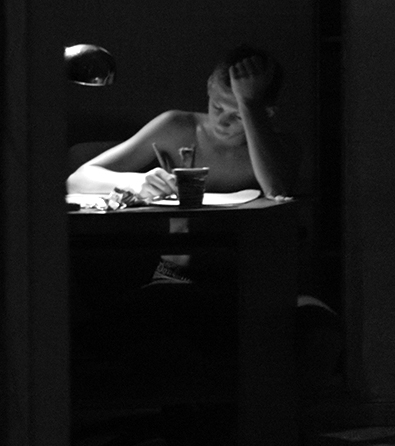

As George and Christina drive home, an argument erupts between them, escalating until it culminates in a brutal car accident. This moment marks the film’s transition from an apparently realistic, everyday scenario to a surreal and disorienting journey. When George regains consciousness, Christina is gone, leaving him to confront the nightmarish world around him. The accident serves as a catalyst, pushing George to muster his remaining strength to return to the party for help, only to plunge into a psychological abyss where the boundaries between reality and nightmare blur.

The visual style of Ronde de Nuit draws on film noir aesthetics, such as sharp contrasts and deep shadows that create an atmosphere charged with tension and dread. As George returns to the estate, the hallways evoke the labyrinthine corridors and disorienting compositions of Alain Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad” (1961), a film that similarly explores the fluid nature of memory, time, and reality. In both films, the characters navigate environments that seem to defy logic and structure, mirroring their inner confusion and emotional turmoil.

The characters, particularly George, are often depicted as small and fragile against a constantly shifting and overwhelming backdrop, emphasizing their vulnerability in the world they inhabit. George’s imposing physical presence offers little advantage as he loses control over the reality around him. The surreal and sometimes abstract visuals are employed to externalize his inner turmoil, with his environment reflecting his escalating anxiety and fear.

At its core, Ronde de Nuit explores the power dynamics between men and women and the constant tension between them. The relationship between George and Christina is fraught with unspoken conflicts, and their argument before the accident hints at deeper issues of control, dominance, and insecurity. This theme is central in both Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut” and Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad.” In “Eyes Wide Shut,” the protagonist, Bill, is driven by a deep-seated fear of his wife’s sexuality and independence, leading to paranoia and doubts about his own sexuality and his ability to please and control her. Similarly, in Ronde de Nuit, George’s journey through the night can be seen as an inward exploration of his insecurities and fears, particularly those related to his relationship with Christina.

Christina’s disappearance after the accident symbolizes George’s loss of control. Her absence leaves him vulnerable, forcing him to confront the darkest corners of his psyche. This dynamic recalls Hitchcock’s portrayal of women in his films, where female characters often become focal points for male anxiety and fear. In Ronde de Nuit, Christina’s absence is as powerful as her presence, haunting George as he spirals deeper into his obsessive thoughts. The film explores similar anxieties about women, sex, and power that Hitchcock examined, particularly the fear of both physical and psychological castration. George’s journey can be seen as a metaphor for his struggle to reconcile his masculinity with the power Christina holds over him, even in her absence.

As George delves deeper into the night, the film becomes increasingly surreal and abstract, echoing the disorienting narrative structure of “Last Year at Marienbad,” which also takes place in a grand estate. In George’s eyes, the space shifts and distorts, reflecting his deteriorating mental state as the world transforms into a labyrinth, trapping him in a cycle of fear and despair. This descent into madness is marked by a series of encounters with women, each one becoming more nightmarish in George’s perception, stripping away another layer of his sanity.

The absence of dialogue in Ronde de Nuit heightens the tension, leaving the viewer to interpret events through audio-visual cues alone. The soundtrack, a blend of ambient noise and dissonant music, plays a crucial role in creating the film’s oppressive atmosphere. Without spoken words, the audience is compelled to engage more deeply with the imagery, allowing Regnard to convey complex emotions and themes without the need for explicit exposition.

Regnard has crafted a film that is not only visually rich but also deeply psychological and thematically complex within the short film format. Drawing on the aesthetics and themes of classic cinema—particularly the works of Kubrick, Resnais, and Hitchcock—Regnard has created a film that feels both timeless and innovative.

The use of Blender’s Grease Pencil tool to create the animation was groundbreaking in 2021. Paradoxically, by showcasing the potential of new and contemporary technologies to expand the possibilities of animation, the film also underscores the enduring mechanical nature of gender power dynamics that have been intrinsic to human existence since time immemorial.

In French, “Ronde” means both a round and a spinning carousel, and Ronde de Nuit appears to nod to another classic film, Max Ophüls’ “La Ronde” (1950), which explores relationships between men and women as they switch partners in search of sexual experiences and happiness with someone other than their partner. Both films examine the often dangerous cycle of relationships, though in different ways: Ophüls’ “La Ronde” employs a carousel-like structure to depict the interconnectedness of romantic encounters across different social classes, offering a playful yet critical view of the pursuit of love and pleasure. In contrast, Ronde de Nuit presents a more introspective and linear narrative focused on the male psyche, with the relationship between George and Christina serving as a lens for exploring deeper fears and insecurities. Nevertheless, in keeping with the Francophile tradition, both films use the motif of spinning, whether literal or metaphorical, to explore the cyclical nature of human desires and their inevitable consequences.