Watch the short documentary film Neighbour Abdi (28 minutes) at the top of the page.

* To watch this film, please approve YouTube/Vimeo cookies via the blue cookie icon at the bottom left of the screen

Dutch filmmaker Douwe Dijkstra is renowned for his meta-cinematic approach, which emphasizes the behind-the-scenes aspects of his work. He adeptly combines various media and fields of creation in his films, integrating documentary realism with narrative photography and production, alongside animation. His short film, Neighbour Abdi, pushes the boundaries of cinematic narrative by blending multiple media within a brief runtime of approximately 28 minutes. Premiering at the Locarno Festival in 2022, the film stands as a testament to Dijkstra’s mastery of diverse cinematic techniques and his commitment to exploring complex human experiences through innovative narrative structures.

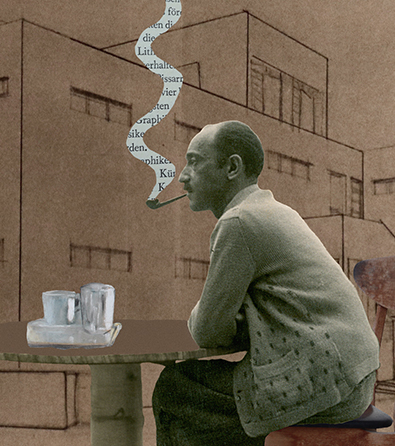

Neighbour Abdi reconstructs the extraordinary life story of its protagonist, Abdi, who actively participates in the film’s creation. The narrative spans his childhood in Somalia, where he faced severe violence, his migration to the Netherlands, and his descent into crime. Abdi’s neighbor, the film’s director, uses his studio equipment to convincingly recreate Abdi’s life. To craft the narrative, Dijkstra employs a range of technical tools, including miniature sets where scenes from Abdi’s life are projected, models of enlarged or reduced objects from the streets, houses, and sites in his life, and a green screen. These elements blend to blur the lines between Abdi’s real-life story, told in the first person, and staged reconstructions from the director’s perspective. This technique enhances the interplay between truth and fiction. Moreover, Abdi plays a central role in the creative process as a co-writer and an active presence in front of the camera, sharing his experiences and guiding the actors and extras in the convincing live reenactment of the scenes.

Dijkstra takes on a versatile role, seamlessly transitioning between his duties as director, cinematographer, sound designer, and visual effects artist. This practical one-man-show approach infuses the film with a sense of artistic cohesion. The music composed by Rob Peters enhances the narrative with tension and emotion.

Neighbour Abdi transcends traditional storytelling boundaries, delving into a meta-level exploration of the intersection between technology and narrative. Through Dijkstra’s innovative approach, the film not only portrays Abdi’s life but also serves as a commentary on the evolving craft of documentary filmmaking in the digital age. As a documentary genre, Neighbour Abdi is an interactive documentary utilizing new media methods while simultaneously being a “living documentary” that allows its protagonist to relive moments from his life through narrative reenactments. The film is not a finished product but rather presented as an ongoing process, offering viewers a behind-the-scenes look at its creation.

In its essence, a “living documentary” highlights the dynamic relationships between the documentary subject and their living environment. For example, Abdi participates in scenes with various sets representing the environment in which he lived in Somalia. His presence on a set that simulates the streets of his neighborhood in Somalia, with the backstage exposed to the viewing audience, makes Abdi’s experience vivid and authentic, reacting genuinely to the reenactment. Therefore, the viewing experience of the film differs from watching a documentary shot on location in Somalia aiming to faithfully represent life at the original location. Instead, the film documents Abdi’s experience as a participant in an artificial and fictional reconstruction, with the film’s authenticity derived from exposing the cinematic viewing tools to both Abdi himself and the viewers.

As an interactive documentary, Neighbour Abdi establishes interactivity as a core component of cinematic creation, emphasizing the transformative potential of digital technologies in reshaping the documentary subject. This transformative aspect is manifested in the reconstructed environment of a sterile film studio, which also carries the emotional dimension of change in both Abdi’s consciousness and that of the viewer. Through its innovative use of technology and immersive narrative structure, the film transcends traditional boundaries, inviting viewers to delve into Abdi’s story—not only in its biographical details but also by engaging with the process of reconstruction itself as an additional layer of his personal story. Dijkstra has created a dynamic cinematic experience by blurring the distinctions between reality and fiction, and between past and present, challenging the conventional concepts of documentary filmmaking.

As the narrative develops, viewers become active participants in Abdi’s journey, navigating between reality and imagination alongside him. In this process, the film acts as a catalyst for introspection and empathy towards the film’s hero, leading to a deeper understanding of his resilience in the face of life’s events. Additionally, the technology, design, green screen, and cinematography sharpen the broader socio-cultural context in which Abdi’s life story unfolds, including the civil war in Somalia and the experiences of African migrants in Europe, particularly in the Netherlands. Abdi is not the unaware foreign immigrant being observed by the camera; instead, he actively participates in the film. The camera does not merely observe him; rather, he looks through the lens, undergoing a process of emotional processing.

The films of Alain Resnais and Chris Marker showcase the profound impact of cinema in exploring the complexities of human experience, particularly in the contexts of trauma, politics, and technological advancement. In works like “Hiroshima Mon Amour” (1959) by Alain Resnais and “La Jetée” (1962) by Chris Marker, these filmmakers delve into the intricate interplay between memory, history, and the mechanisms of modernity. They do so through the lens of the political events of their time and the transformative power of technology in shaping human consciousness.

Artificial recreations through technology are common in cinema as a means of addressing collective and global trauma. In “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” Resnais depicts the trauma of war and the enduring effects of the atomic bomb on the collective psyche through recreations from Japanese films made after the bomb was dropped. Through the split narrative of a romance between a French nurse and a Japanese architect, the film explores the intertwined nature of personal and collective memory. Resnais employs innovative editing techniques to evoke the fragmented nature of memory and blur the lines between past and present, reality and fiction. This fragmentation mirrors the psychological dissonance experienced by the characters as they confront their own traumas while bearing witness to the horrors of Hiroshima.

Similarly, “La Jetée” tells the story of a man haunted by a childhood memory amid the ruins of post-apocalyptic Paris. Through the protagonist’s journey through time via a series of experiments, Marker explores the cyclical nature of history and the persistence of trauma across generations. The use of still images creates a sense of haunting nostalgia that underscores the fragility of memory in the face of technological advancement.

A common thread can be identified between Dijkstra in 2022 and Resnais and Marker eighty years earlier in their engagement with the political upheavals of their time and their use of cinematic and technological means as tools for social critique and political commentary. Alongside many other creators who have used technology and new media to explore the boundaries of cinema, these three filmmakers address technology as a double-edged sword, capable of liberating their protagonists but also possessing the potential for destruction. In “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” Resnais juxtaposes images of modernity, such as the invention of the atomic bomb, with the widespread destruction it causes, highlighting the paradoxical relationship between progress and devastation. The innovative filming and editing techniques and non-linear narratives reflect the influence of modernist experiments in cinema while simultaneously serving as a commentary on the dehumanizing effects of technological warfare and the use of artificial intelligence as a means of mass killing.

Similarly, Marker’s use of experimental techniques in “La Jetée,” such as the combination of still images and narration, underscores the transformative power of technology in reshaping human consciousness. The protagonist’s journey through time via technological experiments speaks to humanity’s eternal quest for transcendence and immortality, even in the face of impending doom. However, Marker also warns of the dangers of technological hubris, as evidenced by the protagonist’s fate.

Like Resnais and Marker, Dijkstra is acutely aware of the limits of new media, artificial intelligence, and the cinematic experiments he conducts in his studio with Abdi’s presence, participation, and even leadership in the narrative. During the film, Abdi acknowledges that the artificial sets, extras, and green screen meant to reenact moments from his life are merely a limited play that, when overly relied upon, can undermine the dignity of history and the many lives it has claimed. The ironic tone in the dialogue between Dijkstra and Abdi underscores their mutual awareness of the limitations of cinematic and technological means in deeply representing the human experience.