Watch the short documentary Requiem for a Whale (15 minutes) at the top of the page.

* To watch this film, please approve YouTube/Vimeo cookies via the blue cookie icon at the bottom left of the screen.

Ido Weisman’s short documentary, Requiem for a Whale, recently garnered the prestigious Best Student Film Award from the International Documentary Film Association (IDA). The film centers around the poignant scene of a whale’s corpse that washed ashore in Nitzanim, Israel, and the diverse group of people drawn to it. The whale’s unexpected presence on the Mediterranean shores, coupled with its death, sparks a range of emotions in the people surrounding it, from wonder and excitement to sorrow and grief. This spectrum of human interactions forms the film’s crux, offering a profound commentary on life and death.

The iconography of the whale developed in history and in the history of art as an image of social chaos. Already in ancient times, commentators in monotheistic religions referred to the image of the whale that appears in the books of the scriptures and the prophets – in Psalms, in the Book of Jonah, in the Book of Isaiah, and the Book of Job. Simply put, the whale’s enormous body protects the prophet from social and political disaster and provides him with physical and mental refuge in a period of chaos. On the other hand, it is possible to find in Midrashim and theological literature of the first centuries AD that it is the whale that forces the prophet to think about the social and political crisis in his country while the prophet resides next to the whale or inside it.

Weisman’s film skillfully intertwines these interpretations, with the camera capturing Israeli society through lenses of compassion, curiosity, irony, and sensitivity. The film features individuals who find solace in the whale’s body. In contrast, others interact with it emotionally and physically, some even cutting its flesh. Paradoxically, the whale’s death highlights the vitality of the people around it, underscoring the social and human crises at the site of its stranding.

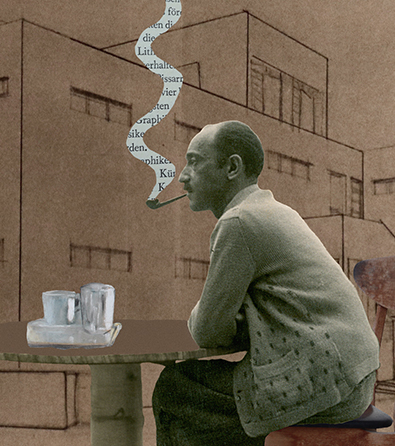

The British political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, in the 17th century, wrote his book ‘Leviathan,’ fully titled ‘Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil.’ This philosophical work, regarded as one of the most influential in political philosophy, was penned against the backdrop of Hobbes’s concerns about the potential collapse of British society and its governing systems due to legal and religious reforms in his country. Hobbes, a supporter of the monarchy, feared persecution by Parliament for his allegiance.

In the book, written during the English Civil War, he discussed the necessity of a social contract between citizens and the ruler to prevent an all-out war. According to Hobbes, the ruler is an entity that stands above nature, including human nature. Throughout the book, he analyzes the relationship between the citizen and the state using the metaphor of the whale and the state of the craftsman: “Seeing life is just motion of limbs […],For what is the heart but a spring, and the nerves but so many strings, and the joints but so many wheels that give motion to the whole body as intended by the artificer? Art goes further in imitating that rational and most excellent work of nature, man. For it is by art that the great Leviathan, called a commonwealth or state (in Latin, Civitas) is created as an artificial man. The arti- ficial man is greater in stature and strength than the natural for whose protection and defense it was intended, and in which sovereignty is an artificial soul giving life and motion to the whole body.” (The Essential Leviathan: A Modernized Edition, Nancy A. Stanlick, Editor, Daniel P. Collette Associate editor, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. 2016)

For Hobbes, the Leviathan is a metaphor for the state – a vast, unique, and complex body built on a societal foundation and comprised of many individuals. Humans cannot fully grasp the existence of the Leviathan, yet it provokes in them the need and desire to contemplate their own existence and the societal structure in which they live.

The focus on whales in modern literature and cinema draws from biblical sources and Hobbes’ political contexts. For example, the award-winning feature film ‘Leviathan’ by Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev, released in 2014, reveals the corruption and social and religious chaos in Putin’s Russia. Using the image of a whale skeleton lying near the protagonist’s home, the director illustrates the relationships between various interest groups and the vulnerable individual, who becomes a victim of their actions and is exploited for their benefit. The film is an adaptation of the Book of Job, using the whale skeleton to discuss the social structure of the country.

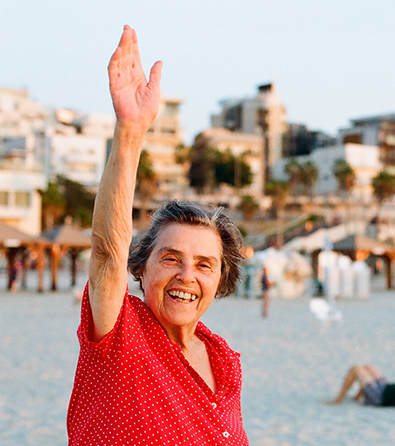

Weisman’s Requiem for a Whale, shot on Nitzanim Beach in Israel, presents a unique documentary scenario unfolding in real time. The director employs a dual documentary approach: one offering captures the human responses to the whale, ranging from proximity to distance, and the other offers an aesthetic portrayal of the whale’s body. This approach juxtaposes the fragility and vulnerability of human society against the imposing, out-of-place figure of the whale on an Israeli beach. The whale’s body in Nitzanim emerges as a primal and existential symbol, drawing various characters and societal groups in 2022, the year of the film’s production. Viewing the film in the context of contemporary Israeli society provokes reflections on the dynamic yet fragile human condition, oscillating between isolation and community, compassion and violence, conflict, and societal division.

The film Requiem for a Whale was produced as part of the Eco-Docu project of the Steve Tisch School of Film and Television, Tel Aviv University, in collaboration with the Heschel Center for Sustainability and the Docaviv Festival.

The short documentary film Requiem for a Whale is available to watch at the top of the page.