MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, is one of Lisbon’s leading contemporary cultural institutions, located on the banks of the Tagus River in the historic Belém district. Inaugurated in October 2016, the museum comprises two distinct yet interconnected buildings: the MAAT Gallery, designed by London-based studio AL_A (Amanda Levete Architects), and the former Tejo Power Station (Central Tejo), a landmark of Portuguese industrial heritage that has been adapted for exhibitions and public programming. Together, they position MAAT as a key destination for travelers interested in contemporary art and architectural innovation.

The Tejo Power Station was built in 1908 and expanded through several construction phases during the first half of the 20th century. It operated as a thermoelectric power station supplying electricity to Lisbon until 1972 and was officially closed in 1975. The building entered a new chapter in 1990, when it first opened to the public as the Museu da Electricidade (Electricity Museum). Following further restoration and rehabilitation, the museum reopened in 2006 in its current, fully developed form, preserving its monumental brick façades, towering windows, and vast turbine halls as a powerful example of early modern industrial architecture.

In 2016, Fundação EDP launched MAAT to expand the institution’s scope beyond the history of electricity and industry and to engage more directly with contemporary art, architecture, technology, and society. Rather than replacing the Electricity Museum, this transformation reframed it within a broader cultural platform. The addition of the new MAAT Gallery, designed by Amanda Levete and AL_A, created a unified campus that connects Lisbon’s industrial past with present-day cultural, environmental, and societal questions.

At MAAT, I visited “Notre Feu,” a compelling exhibition by French artist Isabelle Ferreira, presented in the MAAT Gallery. Ferreira, born in France in 1972 to Portuguese migrant parents, has developed a practice grounded in political and social history, with a sustained focus on economic migration, exile, and inherited memory. The exhibition’s title recalls nights spent gathered around campfires and refers to the clandestine journeys of Portuguese migrants who fled to France in the early 1960s during the Salazar dictatorship.

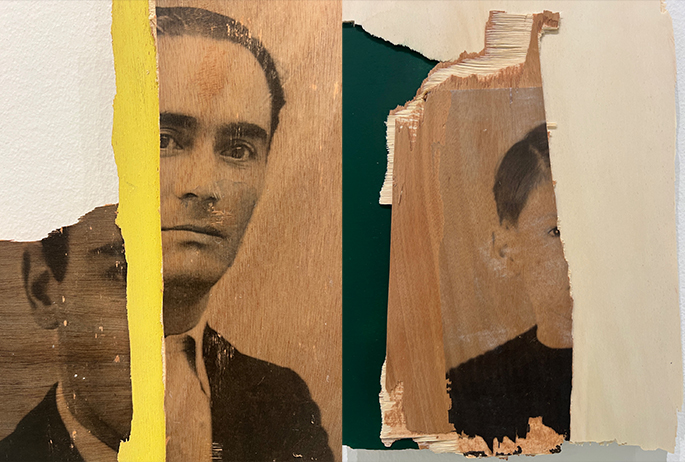

One of the exhibition’s most moving bodies of work, “L’Invention du courage (o salto),” revisits a haunting practice from that period. Before departure, migrants would hand a photograph of themselves to the trafficker, who would tear it in half. One-half was left with the family at home, while the other remained with the migrant and was sent back only after safe arrival. Standing in front of these fractured images, I felt deeply unsettled. The torn photographs, modest in scale yet immense in emotional weight, pushed beyond their historical context and stirred my own family history of Jews fleeing Nazi persecution.

Ferreira constructs an impactful installation through ceramics, wood, torn portraits of those who chose to escape a dictatorship, photographs of landscapes crossed in flight, and large-scale collages of fragmented terrain. Together, these elements convey the danger of the journey toward freedom and transform a deeply personal history into a broader reflection on displacement and resilience.

A visit to MAAT extends well beyond the exhibitions themselves. The museum’s riverside setting invites slow wandering along the river Tagus, where the 25 de Abril Bridge frames the horizon, and the Cristo Rei statue looks out over Lisbon from the opposite bank. Sitting at the museum café, with its open view of the water, becomes part of the experience, offering a moment to pause and reflect. From there, visitors can continue upward onto the gently sloping roof of the MAAT Gallery, where the building turns into a public terrace and the city reveals itself from a new perspective, closing the visit with a quiet yet expansive sense of place.